Evaluation and Improvement of Gene Signatures Using Single-cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA) Dataset in Lung Cancer

Deconvolution of In-House Gene Signature Usage for Better Utilization of Gene Signatures in Clinical Trials

Oncology Data Science Summer Intern Project at Novartis Institutes of Biological Research (NIBR) (2022)

Project Motivation & Background:

As the precision medicine era comes closer and closer, gone are the times when breast cancer patients are all grouped together for a new clinical trial. Clinical biomarker studies that are conducted by pharmaceutical companies reveal the importance of biomarker-driven oncology clinical trials to not only boost the clinical effectiveness of the drug, but also to position their drugs properly in the market. Nowadays, all cancer patients are divided into various tumor subtypes based on a positive/negative testing for certain prognostic biomarkers for that specific type of cancer.

For example, in breast cancer, the first-line therapy for triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) and HER2-positive cancer are different. Additionally, even within a tumor subtype such as TNBC, the first-line therapy may be different depending on whether one tests positive for a BRCA mutation or/and PD-L1 protein. Furthermore, while not a specific protein biomarker, general biomarkers such as tumor mutation burden (TMB) and microsatellite instability (MSI) can both be a great predictive biomarker to determine the best therapy for a patient.

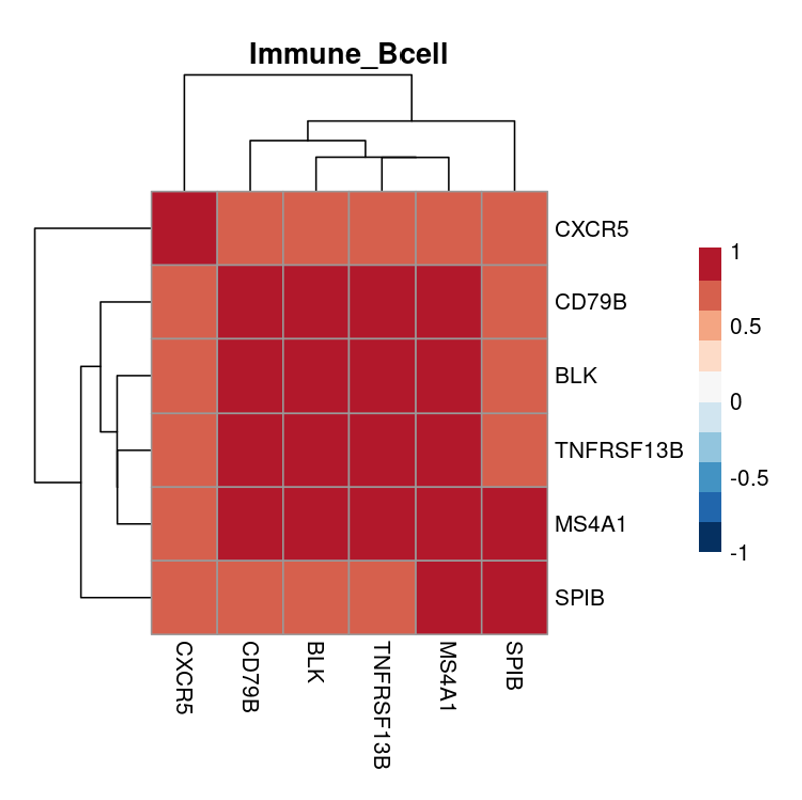

To develop the above tumor subtype differentiation, analyzing the patient’s cancer transcriptome via RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) is the main method to analyze the heterogeneity of the tumor subtype and possibly discover novel biomarkers or therapeutic strategies. From the RNA-Seq data, gene expression signatures (GS) are constructed after pre-processing of the raw RNA-Seq data (QC, normalization, etc). GS are sets of genes that are comprised of multiple individual member genes that show a unique gene expression pattern (GEP), which is a result of a biological or pathogenic process. Below is an example of a cross-correlation heatmap of all pairwise member gene pairs for B cell related GS in lung cancer before applying a cross-correlation coefficient cutoff/threshold to eliminate poorly correlated pairs.

Above, we see several highly correlated genes, with the member genes being all related to B cell function such as activation and proliferation. Compared to evaluating individual gene expression and its correlation to lung cancer, evaluating GS as seen above is statistically much more significant. However, while it is true that these GS can be significant in discovering new prognostic/predictive biomarkers and therapeutic strategies, its potential can be often times exaggerated.

Nowadays, GS are used everywhere in RNA-Seq studies for clinical biomarker studies, and as a result, there are a plethora of different GS that are available (whether the GS is an in-house or publicly available GS). Since GS is constructed from RNA samples, which can be vastly different depending on the experimental conditions and the indication fo the sample as well, we often have numerous GS for a single biological/pathological process- which makes GS highly redundant. For example, a B-cell GS that is different from the one above can be constructed if the experimental conditions, or the patient pool is different. Furthermore, many biological processes (ex. immune cells) are studied at the same time, which results in a GS with significant gene overlap. Therefore, understanding interdependencies among the member gnes of the GS can have implications on how a GS should be used.

Therefore, these redundancies and complexities calls for a method that could be utilized to continuously evaluate, improve, and finally deconvolve the usage of GS in these studies. In this internship project, I worked on seeing if the in-house curated GS called “OncDS GS” and the publicly available and wisely used “MSigDB C6/Hallmark GS” were “good enough”, or applicable to some of the commonly used RNASeq datasets (bulk and pseudobulk single-cell (sc) RNASeq dataset) for clinical biomarker analysis.

Methods:

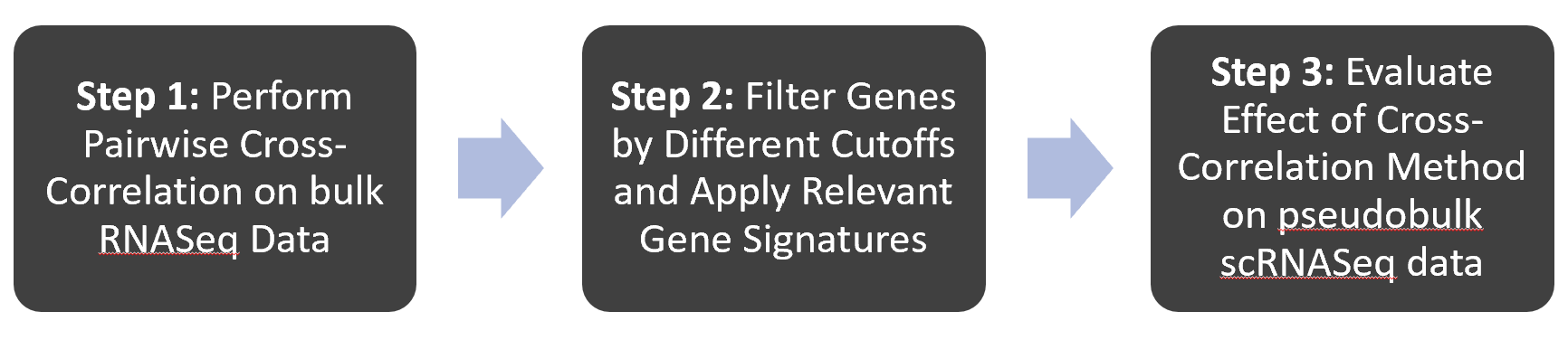

As seen above, there were three major steps for executing the project.

- To perform pairwise cross-correlation on bulk RNASeq data (bulk RNASeq data means no individual cell-type expression data (scRNA), but an average of the cell population expressions) first, the data was downloaded from TCGA and preprocessed in R. Then, Spearman’s Rho pairwise cross-correlation analysis was performed in R for all genes in lung cancer bulk RNASeq data.

- To filter genes by different cross-correlation cutoffs and apply relevant GS, I established three different methods of cutoff that was used to filter the in-house “Onc-DS” GS and the publicly available “MSigDB C6” GS. Then, the different methods of cutoffs were applied and its results were analyzed.

- Lastly, the lung cancer pseudobulk scRNASeq data (pseudobulk scRNASeq is “pseudobulk” because the expression data of a single type of cell is averaged, ex. all CD8+ T cell expression is averaged) was preprocessed in R. Since, these pseudobulk scRNASeq data only has cell populations, we evaluated only the cell-type specific signatures and evaluated if cross-correlation cutoff could improve or refine GS.

Furthermore, we analyze a “gene signature score” (GS score), which is simply the average of the raw read counts of the RNASeq data. The raw read counts of each RNASeq data is the data utilized to calculate the cross-correlation coefficients between member genes of a GS. After applying a cutoff and essentially leaving the highly correlated genes, we can take the average of the raw read counts of those genes and calculate the GS score. This GS score then can be utilized as a metric to analyze how specific and robust these cell-type specific GS are by utilizing the pseudobulk scRNASeq data.

Results:

Note that unfortunately, due to company (Novartis) guidelines, only the results available in the poster are available, and any other results cannot be shown. For the same reason, the pipeline of this analysis, which was fully written in R, cannot be shown either.

The notable results are:

- After applying different cross-correlation cutoffs to both in-house “OncDS” GS and “MSigDB C6” GS, the graphs of cross correlation distribution and example heatmaps in the poster shows that the “OncDS” GS have a higher cross-correlation score (Figure 4), perhaps suggesting that the in-house “Onc DS” GS are more specific, at least in lung cancer.

- After applying the different cross-correlation cutoffs to the “OncDS” GS and analyzing the scRNASeq data to plot a graph (Figure 6) showing GS score vs cell-type for all three cross-correlation cutoff values, we can analyze each cell-type specific GS for its specificity. Some cell-type specific GS such as B cell and Mast cell GS were determined to be specific to their cell type/population, as its GS score was notably higher for their own cell type than the other cell types (ex. B cell GS score is much higher for B cell GS than any other cell types), meaning that the GS is well refined. However, some cell-type specific GS such as CD8+ T cells and NK cells were not very cell-type specific (ex. NK cell GS score is high for NK cell, but also in other cell types). This analysis can show that these GS may need some refinement in the future.

- A caveat of this study is that due to the nature of the pseudobulk scRNASeq data, we can only analyze immune cell-type specific GS. To deconvolve and refine other GS, a more universal method may need to be developed.

Personal Comments:

Q: Why did I choose this project?

After my initial exposure to analyzing RNA-Seq dataset, I wanted more exposure of using bulk and single-cell RNA-Seq dataset to perform more analysis. I was fortunate enough to be picked for this project at Novartis (NIBR), and the project was even more fascinating because the project was related to clinical biomarker analysis team. Even though I could not use the real in-house patient RNA-Seq data from clinical trials in Novartis due to privacy and permission issues, the fact that the project that I would be working on could have an impact in the future biomarker analyses in clinical trials itself was enough to get me hooked to the project. Lastly, it was a different use of a RNA-Seq dataset compared to the first experience I had with it.

Q: What did I do outside of this project?

I made sure to read upon the background of GS, but most of the time I had to kind of re-learn R, since the project was pretty much everything in R (preprocessing, analyzing, plotting, etc). I made sure to review and learn more about the popular packages in R for data science such as dplyr, tidyr, ggplot2, etc and also in-house packages in R that was developed specifically for clinical biomarker analysis.

Q: What impact did this project have on me?

While I can’t downplay the technical skills and knowledge that I gained throughout the internship such as being able to understand GS better and being a better coder in R, the biggest impact was the privilege to be in the middle of an oncology data science group in a big pharma, experiencing everything happening in the company for a couple of months. It’s almost to a point where putting this experience into words would be difficult to do. This also left me with more interest in computational work in oncology, which eventually led me to my master’s thesis research project.

Image credits to: