Gene Delivery Using Lipid Nanoparticle-based Immunoengineering Approach

Development of Targeted mRNA/pDNA Vaccines for Cancer/Malaria Prevention and Protection

Undergraduate Research Assistant Project (2021 ~ 2022)

Project Motivation & Background:

Nucleic acid-based therapeutics have been emergent, as more and more nucleic acid therapeutics are being approved due to their ability to treat diseases by targeting the genetic blueprint itself. Four main types of nucleic acid-based therapeutics are: 1) antisense oligonucleotides (ASO), 2) ligand conjugated small interfering RNA (siRNA), 3) adeno-associated virus vectors (AAV), and 4) lipid nanoparticles (LNP). Recently, more and more nucleic acid-based therapeutics have been approved by the FDA, the most famous being the two COVID-19 vaccines during the pandemic (mRNA- based therapeutic). Recently, the FDA approved Adstiladrin, which is an AAV-based therapeutic for non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC), so more and more nucleic acid-based therapeutics are hitting the market in the oncology space as well.

Compared to conventional therapeutics that usually target proteins that results in transient therapeutic effects, nucleic-acid based therapeutics are often much longer-lasting or even permanent depending on the nucleic acid used and the target. However, most nucleic-acid based therapies require a carrier, as they will be targeted by the immune system for degradation and clearance and therefore will cause unwanted inflammation and toxicity that can be detrimental or even fatal to the patient. Therefore, this project’s research was focused on the design of the lipid nanoparticles, or LNPs, for effective delivery of pDNAs/mRNAs to develop vaccines for malaria/cancer.

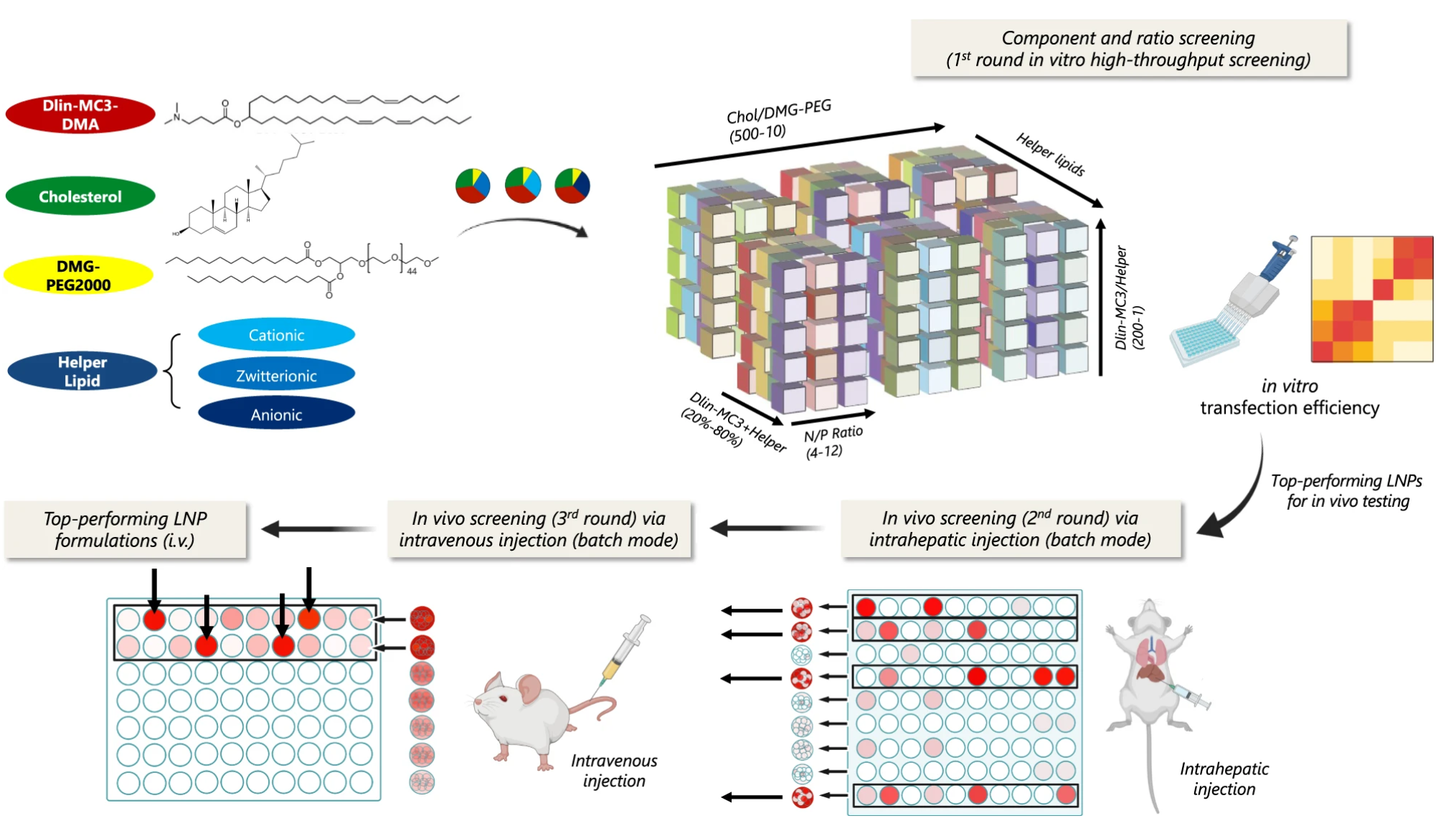

To briefly introduce the background of LNPs, LNPs usually are constituted of four components: 1) Ionizable lipid, 2) PEGylated lipid, 3) Cholesterol, and 4) Helper lipid. The first three components were fixed, and six different helper lipids were explored, with the ratios of the four lipids being varied as well. A total of 1080 different LNPs were designed, with two of the helper lipids being cationic, anionic, and zwitterionic. The ratio and the different helper lipids have a huge impact on the surface charge, pKa, and size of LNPs, which all have a huge influence in the successful delivery of the drug payload. Therefore, the project’s main motivation is not only for successful delivery of the drug payload, but also about optimizing the formulation of the LNP beforehand.

To briefly introduce the two projects:

For the malaria pDNA vaccine project, the proposed route of administration was oral, or through the mouth. This makes sense, as it is a wide known fact that oral drugs experience a “first pass effect”, where the orally taken drugs go through the intestines and end up in the liver. This is why drugs that do not target cells in the liver cannot be taken orally as it is often times metabolized in the liver before it even has a chance to circulate in the bloodstream. In addition, the low pH environment of the stomach due to gastric acid also necessitates a delivery mechanism such as LNPs. However, because the target of the pDNA malaria vaccine is hepatocytes, an oral administration was fitting. Furthermore, pDNA is used rather than mRNA because pDNA has a more long-lasting effect than mRNAs do, however they are therefore more likely to elicit an unwanted immune response, which was known to be alleviated by co-delivery of anti-inflammatory siRNA.

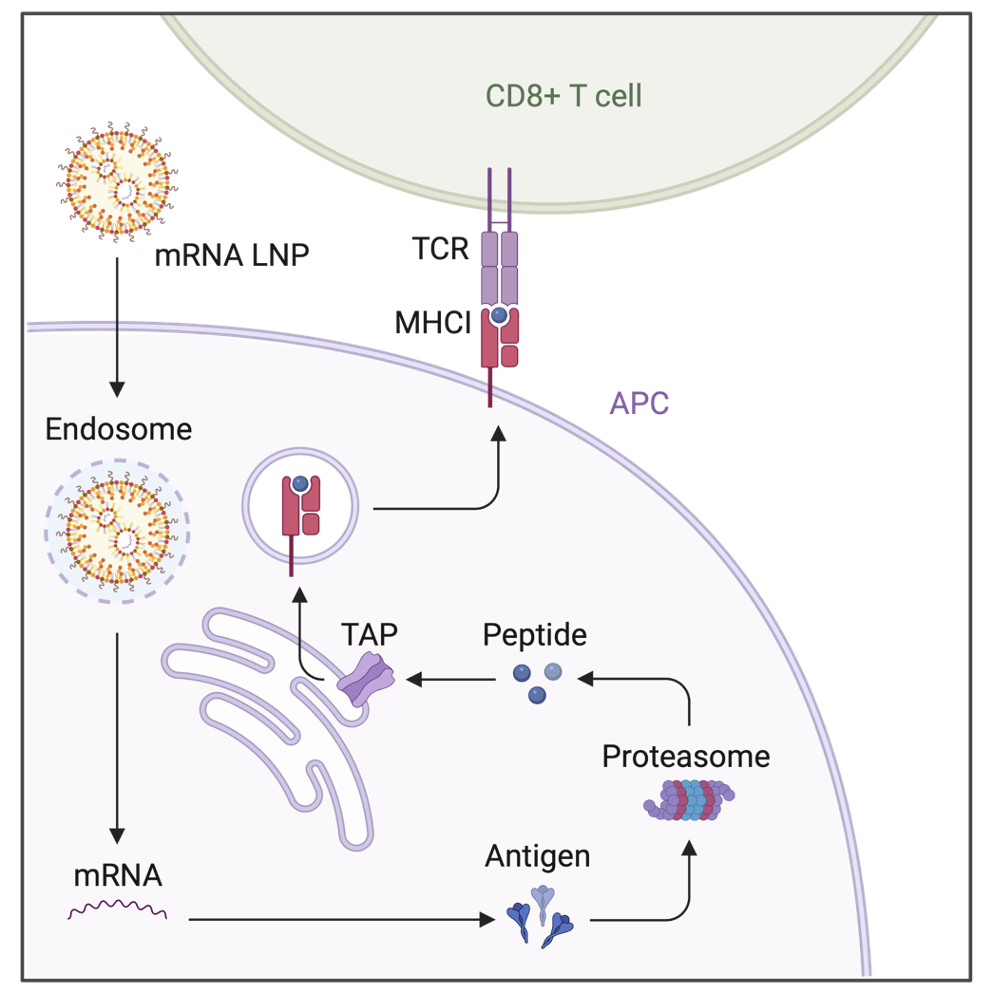

For the cancer mRNA vaccine project, the proposed method of administration was intramuscular, or through the muscle tissue. This is the same route of administration as the COVID-19 vaccines, as it is most effective to elicit a potent immune response. The cancer vaccine can either be prophylactic or therapeutic, but either way, it has to be able to deliver the mRNA that codes for the specific tumor-specific antigens (TSA) that the T cells can recognize and kill the tumor cells. In order to ensure this happens effectively, below is the proposed entire uptake and trafficking scheme of the mRNA LNPs:

As we see above, mRNA LNPs are designed to enter the target antigen-presenting cells (APCs), which in our case are dendritic cells (DCs). They enter the cells via endocytosis, and it is important to design the LNPs in a way so they initiate endosomal escape, or else they are degraded by the lysosomes. After escaping the endosome by breaking the membrane of it, the mRNA is released in to the cytoplasm of the DCs, which initiates translation of the desired TSAs. Now, in DCs, DCs use the proteasome-TAP pathway as a main, conventional route for cross-presentation of the TSAs via MHC Class I molecules. In short, the translated TSA is broken into peptides by the proteasome, and the peptide is translocated by the TAP transporters into the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Then, the MHC Class I complex containing peptides and other molecules are assembled in the ER and transported to the cell surface. Lastly, as seen in the diagram, the CD8+ T-cells recognize the MHC Class 1 complex/molecule via its surface receptor, or T cell receptor (TCR). When this cross-presentation is successful, with the help of other signals called co-stimulary signals, the CD8+ T cell is activated, meaning it can now detect and kill target tumor cells via recognizing their TSAs.

Methods:

The methods for screening the 1080 LNPs for the pDNA malaria vaccine project are shown in below diagram.

Screening Process:

1. Component and ratio screening was done via in vitro transfection for each of the 1080 LNPs. Each LNPs were synthesized and tested for pDNA transfection in human HepG2 cells via using 50% mCherry and 50% Luc pDNA. Then, subsequent luciferase protein expression (more pDNA delivered, more bioluminescence in the cells) was tested and as a result, top 32 formulations for each of the six helper lipids were selected.

2. An in vivo screening via intrahepatic injection was performed, but in batch mode. Just like in COVID-19 testing, where multiple patients’ samples are merged together to test for COVID, the same logic was applied here. 8 of the top 32 formulations were grouped, meaning there were four clusters per helper lipid with a total of 24 clusters tested for intrahepatic injection. The same mix of mCherry and Luc pDNA were injected, and transfection efficiency were determined by imaging the mice liver via in vivo imaging system (IVIS). Furthermore, flow cytometry was used to measure mCherry levels in different types of cells in the liver to see which cells were transfected. As a result, top 12 clusters were selected for having the highest bioluminescence in the liver.

3. Again, subsequent in vivo screenings via intravenous injection was performed, which was in batch mode as well. The same procedure as before was repeated twice, until only top four formulations remained.

Post-Screening Process:

Then, after the screening process was over that left us with top four formulations, a final in vivo screening was performed via using Cre-Ai9 mouse. A Cre-Ai9 mouse, when injected with a Cre pDNA loaded LNP, allows the expression of tdTom only if the pDNA is successfully delivered. Following experiments using confocal imaging and flow cytometry was used to compare the top four formulations effectiveness. Lastly,

The above method was for the pDNA malaria vaccine project, and more details and further experiments are explained in the published paper here. For the mRNA cancer vaccine project, the same screening process can be used, but just in a different applied method:

Screening Process:

1. Component and ratio screening was done via in vitro transfection for the same 1080 LNPs. Each LNPs were synthesized, and tested for mRNA transfection in bone-marrow dendritic cells (BMDCs) instead, since the target is DCs. Then, after waiting for a few days, we collect the BMDCs and co-culture them with CD8+ T cell. Then, we measure level of cell proliferation to test if MHC class I cross-presentation between BMDCs and CD8+ T cells happened or not.

2. An in vivo screening via subcutaneous/intramuscular injection was performed, also in batch mode. Screening based on measuring cell proliferation- cell proliferation will be evident if T-cells are activated by BMDCs.

3. Again, subsequent in vivo screenings in batch mode until top four formulations remain.

Post-Screening Process:

Then, after the screening process was over that left us with top four formulations, a final in vivo screening was performed via using the Cre-Ai9 mouse as well.

Below is a summary of the main work and contributions that I did to each of the two projects, with a list of other detailed experiments not mentioned for brevity.

- In pDNA malaria vaccine project:

- Formulated and screened ~1080 LNPs via cluster-mode in vitro transfection assays and in vivo intrahepatic/intraduodenal injections.

- Tested Ai9 Cre reporter mice for co-delivery of anti-inflammatory siRNA with pDNA for in vivo assays of top formulations.

List of other experiments not explicitly mentioned above: - In vivo experiment with using OVA-SIINFEKL model antigen to determine immunological effects.

- In vivo experiment using Cy5 stain to look at LNP biodistribution.

- ELISA for measuring STAT and NF-κB levels within the liver to determine inflammation levels.

- In mRNA cancer vaccine project:

- Formulated and screened ~1080 LNPs via cluster-mode in vitro transfection assays on dendritic cells, and in vivo subcutaneous/intramuscular injections.

- Tested Ai9 Cre reporter mice for mRNA delivery and participated in subsequent therapeutic and prophylactic mice tumor studies.

List of other experiments not explicitly mentioned above:

- In vivo experiment with using OVA-SIINFEKL model antigen to determine immunological effects.

- In vivo experiment using Cy5 stain to look at LNP biodistribution.

- CCK-8 for measure of proliferation in co-culture of BMDCs and CD8+ T cells.

- ELISA for measuring overall cytokine concentration in the following cell culture supernatant and ELISPOT for frequency of cytokine release.

- ICS (intracellular cytokine staining) followed by flow cytometry measuring cytokine concentration at a cell-type specific manner.

Note that I participated in group discussions/experiments of designing/performing all of the experiments shown above.

Results:

The results of the published paper were mainly the fact that the batch-mode screening process is effective in selecting top performing formulations out of a huge library of LNPs. Furthermore, another major result is that co-delivery of anti-inflammatory siRNA with pDNA alleviates the unwanted inflammation caused by the pDNA and the adjuvant effect of LNPs and therefore extends the duration of transgene expression via pDNA. This is possible due to the STAT and NF-κB siRNA being co-delivered with the pDNA as a payload.

Note that I cannot reveal the detailed methods and results for the mRNA cancer vaccine project since it has not been published yet.

Personal Comments:

Q: Why did I choose this project?

Due to the COVID-19 outbreak, my start to undergraduate research was late, but the mRNA COVID-19 vaccine sparked my interests in gene delivery, particularly for therapeutic gene delivery mechanisms for a prophylactic/therapeutic cancer vaccine. Therefore, participating in these two projects was perfectly in-line with my interests at that time. Furthermore, utilizing and activating the human immune system for preventing/reversing cancer just sounded really cool, as other similar therapies such as CAR-T or immune checkpoint inhibitors were the new "hot" immunotherapies in the oncology space around that time.

Q: What did I do outside of this project?

Before joining this lab, I did not have any practical experience in the wet lab, while I did have some background knowledge regarding LNPs because I took relevant courses in school (ex. drug delivery, supramolecular materials, etc). Therefore, I made sure to review the experimental protocols and analyzed why an experiment was planned the way it is. Lastly, reading articles (journal club) regarding LNPs also helped me to stay up to date with recent discoveries/techniques.

Q: What impact did this project have on me?

Thanks to the kind guidance of the group in the lab, I had the privilege of designing and performing various different wet lab techniques as summarized above. Even though I'm currently doing computational work, I believe the so-called "scientific method" is equal whether it's in the wet lab or the dry lab. Therefore, this has really taught me how to effectively set up an experiment and execute it in the most efficient way. Also, I believe the relative oncology and immunobiology/engineering background that I gained with this experience will eventually help me in the future, even though I've switched over to dry lab. Latly, while not one of the principal authors of the paper, this was my first time contributing to performing experiments and writing a manuscript to be submitted for publication.

Image credits to:

- Scheme of uptake and trafficking of mRNA LNPs (In-house)

- Method to screen 1080 LNPs